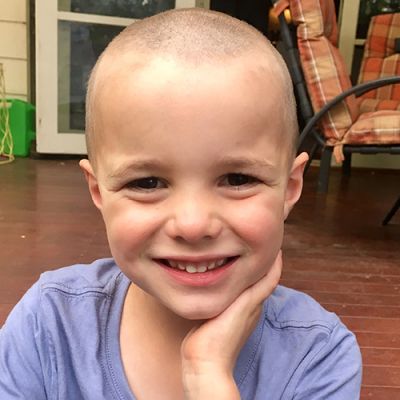

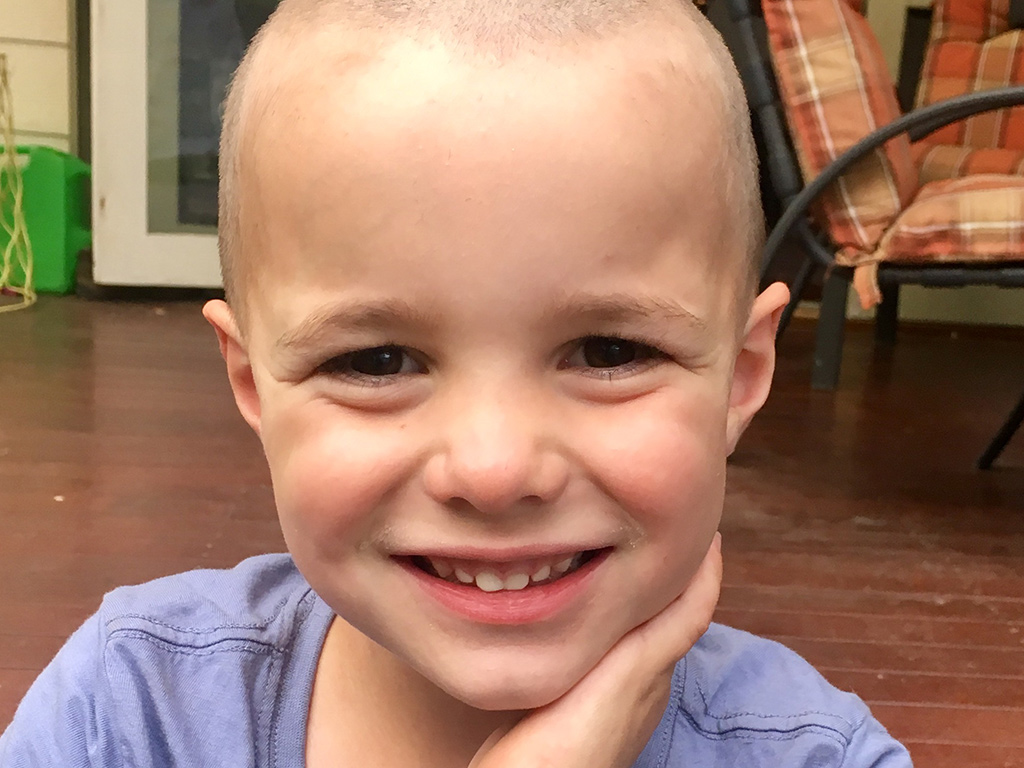

As a baby, Thomas was often unsettled and clingy, never wanting to leave his Mum, Abby. But despite needing regular comforting, he became a regular toddler, a bubbly and energetic little boy.

The first real sign that something was wrong came when Thomas was two and a half years old. He began to consistently feel unwell and vomited a lot.

“We’d go down to our holiday spot every year over Christmas,” explains his Dad, John. “In 2014, we were down at the beach and Thomas was continually vomiting and really lethargic. We ended up taking him to the hospital there.”

At the hospital, Abby and John were told Thomas probably had gastritis. But Abby wasn’t so sure. “I knew that it was something serious, because mothers know these things” she says.

Thomas was rehydrated and discharged from hospital. But the lethargy and vomiting continued, forcing Abby and John to cut short their holiday and head home. They took Thomas to their local hospital.

A few days later, with Thomas still at the hospital, Abby noticed his eye looking odd. The decision was made to transfer him to Monash Children’s Hospital, where he had an emergency MRI. When a team of four people came to get John and Abby after the scan, Abby started to think something serious might be wrong.

“They sat us in a room. I remember seeing a box of tissues on the table and thinking: "What is this room?”

John and Abby were told a large lesion had been found on Thomas’ brain. “I said, "What do you mean by lesion?” says Abby. “Then the doctor said it was a large mass. A very large mass.”

Abby says she had always thought of cancer as ‘an old person’s thing’, and found herself thinking “How does my two-year-old boy have cancer? That’s ridiculous.”

How does my two-year-old boy have cancer? That’s ridiculous."

Abby, Thomas’ mum

But worse news was to come. Thomas didn’t just have one tumour. He had multiple tumours spread throughout his brain, as well as on his spinal cord. Even though the tumors were slow growing, many were located in areas that are inoperable which significantly limits treatment options. Abby and John were crushed. Breaking the news to family that their little boy had cancer was difficult, but John said the hardest thing of all was telling Lucy, Thomas’s sister, who had not yet turned five.

Thomas went into surgery, and John and Abby had an anxious 6-hour wait. “Basically, it’s a situation where you’re waiting for someone to tell you that your child could be dead,” explains John.

The operation went well, but it was still unclear which type of cancer Thomas had. A sample from his tumour was sent to Melbourne, and another to Perth. Frustratingly, a precise diagnosis proved elusive. “They said it was rare,” says Abby. “Something you don’t normally find in a two-year-old.”

They said it was rare. Something you don’t normally find in a two-year-old."

Abby, Thomas' mum

Meanwhile, Thomas developed complications, suffering hydrocephalus (fluid on the brain) and needing surgery to put in a shunt to drain the fluid. As a result of the tumour and surgery, he lost a significant amount of eyesight. Unable to see anything on his left, he started bumping into things, including other children.

Weeks turned into months. Months turned into years. Thomas was in and out of hospital, suffering bouts of vomiting and needing multiple surgeries to clear his shunt which kept getting blocked. Scans were done three monthly, then six monthly, to monitor his progress. Abby and John were despairing.

They offered to help with some cancer research in Germany, where two types of testing done on Thomas’ tumour samples led to two conflicting diagnoses. At around the same time, Thomas’ regular MRI scan showed up a noticeable mass growing in his brain.

“That’s when the doctors started thinking: ‘We’re not entirely sure how to treat this,’” says Abby. “As a parent, it was too hard to even process, thinking that there may be no way forward. We were devastated.”

As a parent, it was too hard to even process, thinking that there may be no way forward. We were devastated."

Abby, Thomas' mum

It was then that Abby and John found out about the Zero Childhood Cancer Program (ZERO). The oncologist said ‘Let’s look at what genetic mutation is causing his cancer, and see it from a completely different angle,’” says Abby.

With Thomas getting sicker and in agonising pain, they were overcome with relief to find out he’d been accepted on the trial. “I don’t know what we would have done without it,” says Abby. “There was no other option for us.”

A sample from Thomas’ tumour was sent for analysis by the ZERO team, and John and Abby waited nervously, not knowing what was going to come back. John says he remembers thinking “If it comes back with nothing, what do we do? We’ve got nowhere to go.”

Fortunately, the analysis showed a mutation believed to be driving Thomas’ cancer, and the ZERO team was able to find a therapy capable of targeting the mutation. In November 2019, Thomas was able to access a paediatric clinical trial using a gene therapy drug called Afatinib. Thomas’s acceptance into the trial was only possible due to the ZERO program which included personalised analysis of Thomas’ tumour sample.

It was a rocky first couple of weeks. Thomas suffered severe gastrointestinal side-effects and had to discontinue treatment. However, after regaining some strength, he was able to start again.

In January 2020, after two months of treatment, Thomas’ brain scan showed a noticeable improvement.

“You could actually see a difference in the size of the tumour,” says John, who says he still keeps a photo of the scan on his phone. “I was so happy, I was hugging the nurses and high-fiving the doctors!”

You could actually see a difference in the size of the tumour. I was so happy, I was hugging the nurses and high-fiving the doctors!

John, Thomas' dad

Over the following days, John and Abby were delighted to see Thomas’s energy levels pick up, his headaches go, and his appetite return to normal.

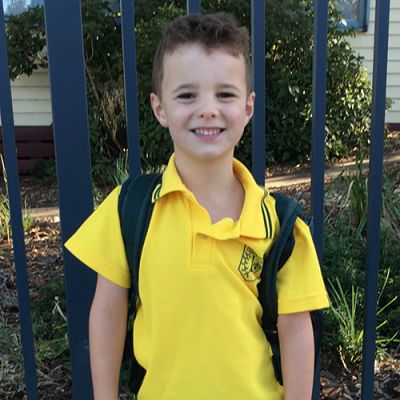

Today, Thomas is eight years old and still receiving the therapy. His tumour has shrunk, and he is no longer in debilitating pain. While the damage to his eyesight is permanent, he has been able to return to activities he enjoys, and he and his family are hopeful for an ongoing return to more regular daily life.

Reflecting back on their journey, John says while he and Abby were extremely unlucky to be in the situation they were in, they consider themselves very fortunate to be where they are now. “We’re in a position where we can potentially put a lot of this behind us. And that’s fantastic.”

Abby says she is very grateful to the clinicians and researchers on the ZERO team. “The work that these guys are doing, it actually changes people’s lives.”

“It’s made a huge difference to us,” adds John. “It makes you so thankful for the little things again. We’ve been reminded just how precious life is.”

As a physician, having the option to get such detailed analysis performed on a tumour is an amazing medical tool that can potentially unlock previously unheard of treatment options.

Dr Paul Wood, Monash Children’s Hospital

In the media

This month, our first major research paper on the results of ZERO was published in the leading international scientific journal Nature Medicine.

Meet Thomas and his family as they talk to 7 News, Tuesday 6 October.

Ellie’s story

Ellie was just 11 months old when a football-sized tumour was found in her chest. It was rare, aggressive and resistant to treatment. With time running out, Ellie was enrolled on the Zero Childhood Cancer Program.

Do you have a story?

If you’ve been touched by childhood cancer we’d love to hear your story